Qatar has dreams of becoming a financial hub and has money to spend, but not everything it needs can be bought, finds George Mitton.

Qatar has dreams of becoming a financial hub and has money to spend, but not everything it needs can be bought, finds George Mitton.

In the ornate lobby of the Four Seasons hotel in Doha, four young Qatari men, dressed in white candouras, sip tea while reclining on velvet couches. A diamond-studded watch glints in the light cast by the enormous chandelier above. Outside the entrance, a cream Bentley purrs to a halt.

For many years, the country with the highest GDP per capita was well known to the funds industry: Luxembourg. But things have changed. By IMF estimates, the honour now goes to Qatar.

The rise of this small peninsula, which extends like a thumb into the Gulf of Arabia, has been astonishing. Who would have believed, 30 years ago, that in 2022 Qatar would host the World Cup?

The sovereign wealth fund of Qatar now owns stakes in Credit Suisse, Barclays and Harrods; the nation’s emir has become a vocal figure in regional politics; and it has been reported that more than one in ten native Qataris is a dollar millionaire.

Qatar would like to establish itself, as Luxembourg has, as a hub for asset management – to provide jobs and diversify the economy away from oil and gas.

And yet, this is not a simple task. Other states in the Gulf share the dream of becoming a financial hub that straddles the divide between the West and Asia. Some, like the United Arab Emirates, are further down the track. Success will depend on factors that cannot simply be bought, but must develop over time, such as an atmosphere congenial to foreign expatriates and a supportive system of law.

But, Qatar’s leaders seem determined to make their financial dreams a reality, and they are not short of money to help make it happen.

HECTIC PACE

The strength of the Qatari economy is not in doubt. After recording the fastest GDP growth in the world in 2010, according to the IMF, the economy is now growing at a slower, though still impressive rate, as the country continues to export oil and gas, and builds hotels, skyscrapers and infrastructure at a hectic pace.

The performance is “excellent”, according to Ahmed Hassan Bilal, a property developer who is among the wealthiest men in Qatar. “The market is open,” he says. “If you want a building permit, [the authorities] will give it to you.”

Bilal is the largest shareholder in the Pearl, a ring of apartment buildings, restaurants and shops built on a man-made island in Doha. He is now seeking to diversify his activities and owns magazines, a furniture company and a Chinese restaurant.

“You may call us greedy because the more we have, the more we want,” he says. “We call it ambition.”

The country’s financial aims are spearheaded by the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC), a free zone in which 100% foreign-owned companies can be established. The centre’s authority, the QFCA, has embarked on a seeding programme to attract international asset managers to set up in Qatar.

The authority channelled $250 million of the nation’s wealth to a private equity subsidiary of Barclays, which is part-owned by the Qatari sovereign wealth fund. Some have wondered if there might be a similar deal with Credit Suisse, in which the fund is also a shareholder.

Seed money of that amount pays a company’s set-up costs, softening the risk of establishing a foreign office. The idea of offering incentives to foreign firms to set up in a new jurisdiction has been employed before, notably by Malaysia.

Shashank Srivastava, chief executive of the QFCA, says the authority is seeking to do more deals of a similar size in the hope of attracting asset management companies with different specialisms. He says the authority is in talks with smaller, boutique firms as well as large international players.

Qatar has home-grown asset managers, though, such as Al Rayan Investment, Amwal, and the asset management divisions of QInvest and Qatar National Bank (see our roundtable on pages 22-28). The local industry is small, however.

Akber Khan, director of asset management at Al Rayan, estimates that assets held in mutual funds domiciled in Qatar are just 460 million Qatari riyal ($125 million), though there is significantly more in segregated or discretionary accounts.

Some feel the Qatari authorities could do more to support the local industry. One professional from a local firm privately expressed disappointment that the QFCA’s seeding programme has so far only yielded a deal with a large international company. It is unfair to give money to international firms without also seeding local players, he said.

BARRIER

However, Srivastava denies there is a bias towards international managers in the QFCA’s programme and says the authority will consider deals with local firms.

Perhaps a bigger question concerns regulation. Local asset managers say a major barrier to launching new products is the requirement to gain approval from Qatar’s multiple regulatory bodies: the Central Bank, the Financial Markets Authority and the Ministry of Business and Trade.

Perhaps a bigger question concerns regulation. Local asset managers say a major barrier to launching new products is the requirement to gain approval from Qatar’s multiple regulatory bodies: the Central Bank, the Financial Markets Authority and the Ministry of Business and Trade.

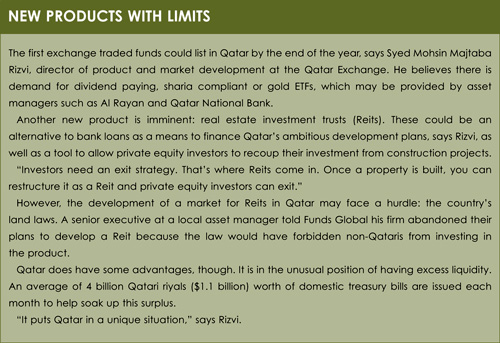

QFC-licensed entities only have one body to deal with, the QFC Regulatory Authority, but if their products are listed on the Qatar Exchange, such as exchange-traded funds, the listing and trading of the units is subject to regulation by the Financial Markets Authority.

Two executives at two local firms, speaking off the record, expressed obvious frustration about the time it takes for the different bodies to process fund documents, and said different bodies sometimes return submissions with remarks that conflict with each other.

There are plans to harmonise the regulatory system. In 2008, the Qatari government said it wanted to combine the Central Bank, Financial Markets Authority and the QFC regulator into a single entity.

Another challenge Qatar faces is to convince its population to put their money into investment products and support a financial industry. Although many Qataris are wealthy, little of their wealth is invested with local asset managers. This is not just true of Qatar. Assets under management in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries amount to just 8% of regional GDP, compared with 63% in Europe and 115% in the US, according to figures from Kai Schneider of Latham & Watkins in Dubai.

Instead of giving money to local managers, Qataris often hold money in their family businesses, invest it with asset managers abroad, or invest directly in stocks. There is no private pension system in Qatar, though there is a public one, and the many foreign workers in the country tend to send money home rather than invest it locally.

Like the rest of Qatar’s financial system, the stock market is still developing. In August, there were 43 listed stocks and the market capitalisation was a little below $300 billion. Equity managers do not have a lot to choose from in Qatar, since many big companies they might wish to access, such as Qatar Petroleum and others, are state-owned and unlisted.

Syed Mohsin Majtaba Rizvi, director of product and market development at the Qatar Exchange, admits there is a risk investors will lose their enthusiasm for trading if there are no new companies listed. He says there are initial public offerings (IPOs) coming, though would not name the firms.

If one of these IPOs was from a high-profile state-owned company, it could be a catalyst to trading. The nation’s airline, Qatar Airways, might be a candidate. But it is unlikely that executive boards will make the decision to list while the global economic environment is still uncertain. In the meantime, Rizvi is hopeful that debt IPOs will stimulate trading activity.

SURROGATE

Some investors are excited about Qatari equities, despite the limited size of the stock market. Although it is not possible to invest directly in the state-owned hydrocarbon industry, investors can buy stocks in Nakilat, a natural gas shipment company, or Industries Qatar, which produces fertilisers and other products made with petrochemicals.

The biggest sector on the exchange is banking, which some fund managers view as a surrogate for the wider economy.

David von Simson, chairman of Qatar Investment Fund, a London-based fund investing in the Qatar Exchange, says the relatively small size of the stock market and the lack of liquidity on some stocks does not prevent his team from making interesting investments. “There’s certainly enough here to be keeping us busy,” he says.

It is likely that the Qatari economy will continue to boom for some while yet, provided natural gas prices do not fall sharply. The authorities have committed to huge infrastructure projects worth either $225 billion or $300 billion, to pick two estimates. Some of these projects are stadiums and hotels for the World Cup, but there are plans for hospitals, transport hubs and more.

Among these schemes, Qatar’s dream to be a financial hub shows promise, but there is much work still to do.

©2012 funds global