After alarming social unrest, why have a handful of companies set up shop in Bahrain? A qualified labour force, proximity to Saudi Arabia and a trusted regulator are three reasons, finds George Mitton.

After alarming social unrest, why have a handful of companies set up shop in Bahrain? A qualified labour force, proximity to Saudi Arabia and a trusted regulator are three reasons, finds George Mitton.

Bahrain was the first country in the Gulf to have a finance industry, established by bankers fleeing civil war in Lebanon. In the early 1980s, Bahrain-based Investcorp united wealthy investors across the region in its pioneering private equity company, which now manages $11.5 billion of assets from offices in Bahrain, New York and London.

Yet in recent years the island kingdom has lost business to its younger, brasher neighbour, Dubai, which has attracted more than 300 financial companies to its financial free zone, the Dubai International Financial Centre.

Then, in 2011, protests against the Bahrain government – seen by many as an episode of the Arab Spring – drew a crackdown from the authorities that brought international scorn and left an uneasy tension in the kingdom.

While political unrest has simmered in the past 22 months, a number of international asset managers have partially or fully withdrawn from the country, seeming to underline the falling fortunes of the Gulf’s oldest financial centre.

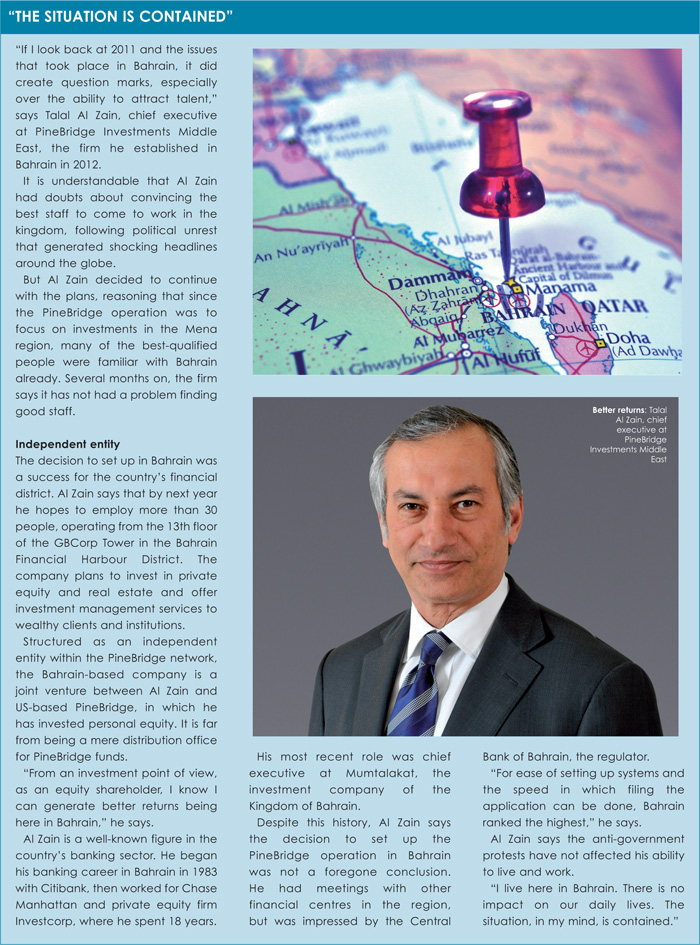

And yet, amid the reports of violence, one US asset manager, PineBridge Investments, has established a regional headquarters in the country, an operation that aims to employ more than 30 people and handle investments into the Mena region and Turkey (see box). Swiss private banks, Notz Stucki and Altaira Wealth Management have set up in Bahrain, too.

Each has a similar story. They say preparations began before the protests and that the advantages of establishing in Bahrain, such as its regulator, the Central Bank of Bahrain (CBB), outweighed concerns about the unrest.

However, there is no doubt that ongoing reports of violence in Bahrain are distressing. The report of an inquiry into the 2011 crackdown, chaired by Professor Cherif Bassiouni, accused the government of illegal arrests, forced confessions and systematic use of torture. King Hamad subsequently promised human rights reforms. Protests continue despite the Bahrain government banning all public rallies and demonstrations in October.

WOUNDED REPUTATION

The events have wounded the reputation of the kingdom, though some in the business community remain stoical.

“We’ve lived through two Gulf wars. We’ve had Scud missiles. We’re not leaving over this,” says a senior source at a Bahrain bank who asked to remain anonymous.

Some financial companies decided they were leaving, though. It was reported that Crédit Agricole, from France, Robeco, from the Netherlands, and Nomura, from Japan, moved their regional headquarters from Bahrain to Dubai.

Frankfurt-based Allianz Global Investors, which had a small presence, withdrew at the beginning of this year, according to a marketing officer in the country.

Other firms have hedged their bets.

Though BNP Paribas is still present in a large office, it has opened a back-up operation in Dubai. Dexia Asset Management opened a representative office in Bahrain in 2006 and is still present in the country, but in November last year also opened a representative office in Dubai.

However, a brochure from the Bahrain Economic Development Board lists a number of asset management companies that are still present in the kingdom. Credit Suisse and Lazard Asset Management are still there, as attested by company websites. Bahrain recently welcomed Swiss bank BSI. Meanwhile, Citi increased staff numbers in Bahrain in 2011.

‘BAHRAINISATION’

Boyd Winton, director of financial services at the Bahrain Economic Development Board, says some withdrawals came, not because of unrest, but because banks were cutting costs in the wake of the financial crisis.

Though there was “some short-term economic impact from the unrest”, he says, the long-term investment case in Bahrain “remains compelling”.

He concedes the number of enquiries for new business has fallen since the protests began, but insists the number of people employed in financial services in Bahrain has not declined.

Part of the attraction is Bahrain’s labour market. There is no “Bahrainisation” programme that would force companies to employ a certain percentage of locals as there is in other Gulf states – because there doesn’t have to be. Unlike other Gulf states that rely heavily on expatriate workers, a significant portion of Bahrain’s workforce is local, and many of them are qualified in finance.

A report by professional services firm KPMG that will be published in January says it costs 25% less to run a financial company in Bahrain than in the Dubai International Financial Centre and 40% less than in the Qatar Financial Centre.

“The experience of those inside Bahrain, where businesses are continuing to expand… is more optimistic than the perception from outside,” says Winton.

The CBB is another advantage. Established 30 years ago, the regulator is reckoned to be efficient and competent, says Altaira Wealth Management, which set up a Bahrain office in 2012 with a “category three” licence, which means it can arrange deals and advise on investments.

Every financial firm has to have a compliance officer in Bahrain, while the UAE allows companies to outsource this function, says Frederick Bastin, compliance and operations manager at Altaira in Bahrain. He believes this strictness is a benefit as it shows clients that a firm based in Bahrain is reputable and well-managed.

‘UMBILICAL CORD’

Practical matters are also appealing. Anthony Acampora, chief executive of Altaira, says good office space is available at reasonable prices, along with a sophisticated investment community.

“Anyone looking at the region and comparing costs should take a hard look at Bahrain,” says Acampora. “In the next few years I think we’ll see some big companies coming in.”

Perhaps the most important factor, though, is Bahrain’s proximity to Saudi Arabia, the home of several of Altaira’s shareholders. Bahrain is connected to the east coast of Saudi Arabia by the King Fahd Causeway, which Acampora calls the country’s “umbilical cord”.

Saudi Arabia has a population of 27 million, compared with a little over a million in Bahrain. Because of its size, Saudi Arabia is a crucial market for investment companies operating in the region.

Notz Stucki, another Swiss private bank, which established a representative office in Bahrain, has key clients in Saudi. Maria-Sofia Kourti, head of Middle East for the company, says proximity to these clients was one reason why, after a two-year feasibility study, the company chose Bahrain.

Another was the CBB. In 2008, Notz Stucki began redomiciling its funds from Bermuda to Luxembourg. When it looked to establish a base in the Middle East, it wanted a regulator with similar standards. Bahrain is already the domicile for many funds run in the region because of the CBB’s reputation.

“We wanted a regulatory environment that supported our aim to be a local asset manager,” she says.

The anti-government protests were worrying to the company, says Kourti, but Notz Stucki finally decided the protests were an internal political issue that were unlikely to affect the company’s business.

Others may not agree, however. Clearly, there are many benefits to Bahrain, but as allegations of human rights abuses continue, the country must work hard to restore its reputation.

©2012 funds global mena