While tear gas billowed over Tahrir Square, Egyptâs fund industry suffered heavy losses. However, a stock market surge and the prospect of an elected president hint at a recovery. George Mitton investigates.

While tear gas billowed over Tahrir Square, Egyptâs fund industry suffered heavy losses. However, a stock market surge and the prospect of an elected president hint at a recovery. George Mitton investigates.

A couple of years ago, a mutual fund launched in Egypt might have targeted EGP100 million (€12 million) and closed at double or triple that, recalls Omar Radwan of Cairo-based HCSI Asset Management.

“Unfortunately, [in 2011] the targeted size has been about 50 million and we’ve seen some that were only looking to collect 25 million and were barely able to close,” he says. “The numbers don’t lie. It just sums up the whole thing.”

It was inevitable that Egypt’s funds industry would be affected by the turmoil of the past year. Thousands occupied Tahrir Square, president Hosni Mubarak was ousted after 30 years in power and a military junta suspended the constitution.

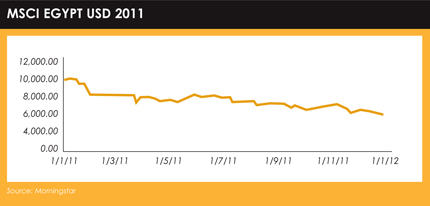

The effect of the disruption on Egypt’s capital markets was dramatic. Foreign direct investment plummeted, a gaping trade deficit appeared, and the MSCI Egypt index lost almost half its value during 2011. Egypt’s foreign reserves have been depleted, meaning the country may need to resort to devaluing its currency, an event that often kick-starts inflation. At the time of writing, Egypt’s military rulers had just asked the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $3.2 billion (€2.4 billion) loan.

Funds under management in Egypt have declined as a result of the unrest. Zawya Funds Monitor estimates that assets under management of Egypt-domiciled funds were $7.6 billion in the third quarter of 2011, nearly $2 billion less than at the end of 2010.

The Egyptian Investment Management Association lists 81 funds operating in Egypt as of the end of 2011.

The largest equity fund by assets was the Shield fund run by Arab African Investment Management with EGP240 million, while the biggest bond fund was the Thabat fund from CI Asset Management with EGP270 million.

Radwan, who is chief operating officer at HCSI, says his strategy in the face of the volatility was simply to limit the damage. He sought to reduce exposure to the stock market and promoted fixed-income and money market funds instead, though his efforts were frustrated by a drying out of liquidity. “To save our investors, we had to lower the [equity] exposure a little bit, but we couldn’t mitigate the whole hit,” he says, adding: “When there is this kind of fright, people run to safety. The investment cycle slows down.”

Last year’s financial figures were disappointing for a country which many investors thought would be among a new wave of emerging economies. Egypt is the E in the acronym Civets (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Thailand and South Africa), a grouping that was trumpeted as a successor to the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India and China).

Michael Geoghegan, the former HSBC Group chief executive, coined the term and HSBC Global Asset Management was the first to launch a Civets fund in May 2011.

Transition

HSBC is still bullish about Egypt’s growth prospects, though it is sticking to long-term, speculative predictions. In a recent report, it predicts that Egypt will overtake Saudi Arabia as the largest economy in the Middle East and become the 20th biggest economy in the world in 2050. HSBC says Egypt’s GDP will leap from $160 billion in 2010 to $1.2 trillion in 2050, implying annual growth of about 5%.

However, Egypt will have to pick up its growth rate in future years to compensate for a current rate that is estimated at between 1% and 2% this year.

HSBC’s report is not all rosy. Per capita income in 2050 will still lag behind the developed world at less than $9,000, it claims. This is less than a third of today’s per capita income in the UK.

However, all this growth depends on Egypt finding jobs for its population, particularly for young people. IMF officials say a quarter of Egyptian youths are unemployed – deeply problematic for a country where the majority of its 80 million population is under 30.

“The key story in Egypt is demographic,” says Tarek Osman, an Egyptian writer and author of Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to Mubarak, who addressed a recent debate on the country in London.

“Look at 45 million Egyptians who are under 30 years old, who effectively cannot and will not be represented or accepted by the remnants of an old regime… a military establishment represented by people the age of their grandparents.”

It is important that the protesters do not feel their fight is over. Mubarak may be gone, but what Osman describes as the “remnants” of the regime are still in power, in the form of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, led by Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi.

The military is committed to holding power while Egypt elects new rulers.

However, there are promising signs that there will be an orderly transition to a new government. Egypt recently held parliamentary elections, with the Freedom and Justice party, the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, winning 46% of the seats in the Egyptian parliament. Presidential elections are scheduled in coming months and the country’s politicians are working on a draft constitution.

The markets have responded with a huge boost in confidence. After its bad performance in 2011, the Egyptian stock market is now the best performing market in the world with around 28% growth in January alone.

The rally has helped offset last year’s losses. Nabil Moussa, managing director of asset management at EFG Hermes, saw his portfolio suffer heavily last year. He tried, with limited success, to mitigate the damage by switching into defensive sectors such as petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals and telecoms.

But in December he saw signs that the market had hit the bottom and began buying riskier stocks again. This year, his portfolio has participated in a “beautiful” rally that has helped offset many of last year’s losses.

“It’s a matter of confidence,” he says. “The real Egyptian economy is intact.”

Moussa claims that despite the bad performance, he did not lose any accounts in 2011. This may be due to the reputation of EFG Hermes, which is well known in Egypt, having launched the country’s first mutual fund in 1995.

However, Moussa accepts that Egypt’s trade deficit must be fixed for it to achieve a recovery, and says IMF money is vital. The Egyptian politicians “know well that without an IMF deal we will have a balance of payments crisis”, he says.

Another important factor will be whether the other Arab countries honour a pledge to provide $10 billion in assistance to Egypt, on top of the IMF loan. The country also needs tourism revenues to pick up.

This is possible, says Moussa, though Egypt must avoid a repeat of events such as a widely reported disaster at a football stadium in Port Said in the north east last month, when a riot and stampede killed 74 people.

Modernisation

“If we get between $10 billion and $15 billion, and with a recovery in the tourism industry, which was hit badly, I think you’ll see a major turnaround in the economy,” says Moussa.

With a return to stability, there may also come the first of a range of changes in the Egyptian funds industry that could make the nation more competitive. Currently, there are no exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in Egypt, no derivatives and no short selling. The capital market authority was close to launching the first ETF at the beginning of 2011 and was studying the introduction of derivatives, but the political turmoil got in the way.

Radwan says there are no technical barriers to introducing new instruments. “The IT infrastructure of the stock market is state-of-the-art,” he says. “We can take on ETFs. Our system can allow derivatives. In theory, we are ready to launch.”

Modernising Egypt’s capital markets requires political will, however, and Egypt’s politicians have other priorities right now. But towards the end of this year, barring further unrest, the conditions could be set for change.

There is also the potential to create a market for corporate bonds. In the past, Egyptian companies financed themselves solely with bank loans and it was difficult for other lenders to join the market. Radwan describes this as a structural problem that could be solved by mimicking the model of other countries which have developed corporate bond markets.

Radwan, an optimist, hopes to see a range of measures that would improve Egypt’s capital markets. “My wish list: I would love to see pension funds modernised to allow pensioners to have an active say and become real clients of the asset management world. I would love to see the fixed-income market tweaked and become more active. I would like to see derivatives or at least an ETF launched on the Egyptian market.

“This list sounds big and looks big but if you look at them you’ll find that we’ve been preparing for years. We have all the ingredients to be a financial centre for the Mena region – in terms of time zone, professionals, legal infrastructure, everything.”

“This list sounds big and looks big but if you look at them you’ll find that we’ve been preparing for years. We have all the ingredients to be a financial centre for the Mena region – in terms of time zone, professionals, legal infrastructure, everything.”

©2012 funds global