After years of rumours and false alarms, Saudi Arabia is finally opening its stock market to direct foreign investment. What does it mean and why does it matter? George Mitton reports.

After years of rumours and false alarms, Saudi Arabia is finally opening its stock market to direct foreign investment. What does it mean and why does it matter? George Mitton reports.

It was only a few days before the Eid holidays in the Gulf countries. Ramadan, which occurred this year during the baking hot days of June, was about to come to an end and many in the financial sector were looking forward to a holiday.

Just the time, then, for the Saudi cabinet to drop the biggest bombshell to hit the regional capital markets in more than a decade: the Saudi stock market, the Tadawul, would open up to direct investment from qualified foreign institutions.

The Tadawul is huge, by regional standards. With a market capitalisation of about $580 billion it is the biggest stock market in the region by far. If it were to open fully and enter the MSCI Emerging Market index it would have a similar weighting to Mexico. No wonder, then, that fund managers were excited by the news. Within hours the Saudi regulator, the Capital Market Authority (CMA), had confirmed it would oversee the opening-up process, scheduled for the first half of 2015.

Now that this event is finally happening, what does it mean?

LOOKING BACK

Investors outside the Gulf have been able to access the Saudi equity market since 2009 by using swap arrangements. It was an arrangement that suited some but not others, who disliked the lack of control, counterparty risk and no voting rights. For them, the much-heralded plan to open the market to direct investment by qualified foreign institutions, something like what China did when it opened up its market, was appealing.

Yet the opening of the Tadawul had been talked about for so long, with no sign of action from the Saudi authorities, that some had begun to say it would never happen at all. There had been several positive signs that had come to nothing: in early 2012, news reports circulated that senior bankers had worked with the Saudi authorities on a time line for opening up, but the news faded away with no progress.

Some even began to declare that the Saudi market would never open up. According to this view, the Saudis had no motive to welcome foreign investment. After all, Saudi Arabia has tremendous oil wealth and the Tadawul was already large and liquid. What use had they for foreign capital?

In fact, opening the stock market does make sense in the context of the Saudis’ broader objective to diversify the economy away from oil and to provide jobs for its citizens. “To do this successfully will require attracting overseas investment, and having a fully functioning capital market goes hand-in-hand with that,” says Ghadir Abu Leil-Cooper, head of EMEA and frontiers equity team, Baring Asset Management.

Does it follow that foreign institutions will want to invest in Saudi stocks? Yes. Not only is the Tadawul large and liquid, it has a depth of stocks and sectors that other regional exchanges can’t match. Saudi Arabia has the largest population in the Gulf, many of whom are young, and its currency is pegged to the dollar. And it has those oil reserves – estimated to be the second largest in the world.

“Saudi Arabia’s economic output, the size of its equity market and its demographics all vastly outstrip those in the remainder of the GCC countries,” says Bassel Khatoun, head of MENA equities, Franklin Templeton Investments. Based on these factors, analysts have predicted large inflows from foreign investors. Assuming foreign participation in the Saudi stock market rises to levels comparable to other regional exchanges, there will be an inflow of more than $30 billion, on top of the roughly $4 billion that foreign investors have managed to accumulate since 2009, by using swaps.

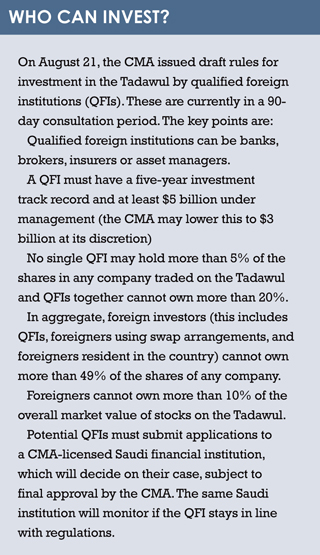

However, inflows might not be as large as this, at least not initially. According to draft rules released by the CMA, participation will be limited to foreign institutions with a five-year investment track record and at least $5 billion under management. Once qualified, these investors will face numerous foreign ownership limits such as a cap of 5% per qualified investor per stock and a market wide cap of 10% on the value of the Tadawul (see box on page 11).

These restrictions will limit how much foreign money flows into Saudi Arabia. According to a conservative estimate from bank HSBC, the inflow might be $9 billion, a smaller but still considerable amount of money in regional terms.

The aforementioned limits will affect whether Saudi Arabia is admitted into the MSCI Emerging Market index. Should the index provider award this status, the Tadawul will become more visible, gain credibility and attract more inflows, as happened to Qatar and the UAE when they were awarded emerging-market status earlier this year. It is widely assumed to be the goal of the Saudi regulators to achieve this status eventually.

But foreign ownership limits may stand in the way.

“Saudi Arabia is broad and deep enough to warrant a potential inclusion in the emerging market index,” says Sebastien Lieblich, executive director of index research, MSCI. “Accessibility is the big question mark,” he adds.

After the Tadawul opens to direct foreign investment next year, MSCI will begin consulting with its clients. If the clients find that the CMA’s limits unduly hamper their ability to invest in the Saudi market, the index provider will not upgrade Saudi Arabia to an emerging market.

MSCI will also look at the process for awarding investor licences to see if it is transparent and fair.

Foreign ownership limits by themselves are not necessarily a hindrance. Qatar achieved emerging market status while keeping foreign ownership limits in place, though Lieblich points out that the country did raise its limits significantly, and says this was a reason for Qatar’s upgrade.

Another issue that could prevent Saudi Arabia’s transition to an emerging market would be complications around the country’s T+0 settlement system, which is out of sync with the common international system, T+2. Trying to mesh the two systems will cause problems for brokers and custodians in the country and if this impairs foreign direct investment, it could count against Saudi Arabia in MSCI’s consultation. (For more information on the T+0 issue, see our asset servicing roundtable, pages 30-36.)

If MSCI decides not to make Saudi Arabia an emerging market, it will either remain unclassified, as it is now, or enter the frontier market index. Although foreign ownership limits are unlikely to be an obstacle to frontier market status, Lieblich says MSCI will be cautious about awarding this status to Saudi Arabia, because its weight in the frontier market index would be large, perhaps more than half the index on some estimates. The entry of such a large component could destabilise the frontier market index, and MSCI would want to avoid this.

If MSCI decides not to make Saudi Arabia an emerging market, it will either remain unclassified, as it is now, or enter the frontier market index. Although foreign ownership limits are unlikely to be an obstacle to frontier market status, Lieblich says MSCI will be cautious about awarding this status to Saudi Arabia, because its weight in the frontier market index would be large, perhaps more than half the index on some estimates. The entry of such a large component could destabilise the frontier market index, and MSCI would want to avoid this.

It should be added, though, that the consultation on Saudi Arabia’s status will not happen for some time. Lieblich says Saudi Arabia may enter its watch list in June 2015 with a potential inclusion in the emerging market index in 2017 at the earliest.

WHAT IT MEANS

When it happens, the opening up is likely to bolster the Saudi exchange. Liquidity will most likely improve, trading volumes will rise and transaction costs should fall. As foreign institutions such as large asset managers become shareholders in Saudi companies, the exchange ought to become more stable.

These institutions are long-term investors, unlike the majority of today’s Saudi investors, who are retail and high-net-worth and often use leverage to enlarge their gambles, contributing to a highly volatile market.

Another effect of the opening up could be an improvement in corporate governance, as direct shareholders gain voting rights that they lacked when investing via swap arrangements.

“The decision to allow investors to own the shares directly and exercise voting rights will spur the concept of activist shareholders in the kingdom, as opposed to a purely monetary participation in the listed companies before,” says Muhammad Anum Saleem, senior associate at law firm D&P Dhabaan and Partners.

The result could benefit Saudi companies, who would receive management, accounting or legal guidance from their investors. In time, fund managers in the region hope this trend will lead to more disclosure and transparency, which will improve the quality of research on Saudi equities.

CHANGE IN MINDSET

However, there are caveats, one being that not only regulation but also a change in mindset may be required to instil the values of foreign activist shareholding in the Saudi market. Some warn that although the presence of foreign investors will have long-term benefits to the market, in the short term it may dismay some Saudi firms, especially if they are nervous of ceding control of their business to foreign parties.

“There are a lot of family conglomerates, with, say, 20% on the Tadawul,” says Khalid Murgian, managing director of Neuberger Berman in Dubai.

“It will be anathema to them that some foreign manager can come and tell them how to manage their business. The opening up may have a perverse effect of having fewer companies come to market.”

If the opening up does cause a slowdown in initial public offerings (IPOs) in the country, this would be a blow to the regulator, which is trying to promote a vibrant capital market.

The onus will be on the CMA to educate companies about the benefits of having foreign shareholders in contrast to what they may see as the threats.

Other problems might confront those financial firms who want to set up a presence in Saudi Arabia as a result of the changes.

“We don’t want to confuse Saudi Arabia opening the equity market with them going far down the road of being an open market,” says Murgian. “It’s still the hardest country in the region to get visas for. Setting up a business there is time and resource consuming.”

Because Saudi Arabia is a comparatively difficult place to do business, the opening up process may turn out to be a boon for nearby jurisdictions such as the UAE rather than for Saudi Arabia.

Asset managers who want to increase their presence in the Gulf to capitalise on investment opportunities in Saudi Arabia might decide to base their staff in nearby Dubai, for instance, where the supporting infrastructure is better and where western staff can enjoy a lifestyle more like their own. Saudi Arabia does want to attract foreign financial firms. It is trying to address the lack of good quality office space, for instance, by building the King Abdullah Financial District.

However, there will be the inevitable culture shock for most westerners who choose to move to Saudi Arabia, with its strict rules on everything from alcohol to shop opening hours and gender segregation.

What the opening up process could mean is a boon for local, qualified Saudi workers, who would be the ideal recruits for international firms looking to develop a Saudi equity investment capability.

“I think it’s a great opportunity for smart young Saudis who run Saudi equities,” says Murgian. “They become immediately more eligible and more interesting for people looking to hire.”

Perhaps Saudi equity managers and analysts should start tightening up their CVs. For analysts and fund managers elsewhere, it may that despite opening up, Saudi will continue to be covered at a distance, though perhaps that distance will shrink to the space between Dubai and Riyadh.

©2014 funds global mena